The Gordon Bombay Extinction Button

In an era of unprecedented radical children's films, Gordon Bombay is the neoliberal scum with an imperialist agenda as he loses his way part of the way through a potential revolution.

Note: This post is pretty spoiler heavy on the Mighty Ducks series and one particular episode of the X-Files. If you don’t want to read spoilers, or simply don’t care (I get it), I’d recommend skipping this one.

"The Mighty Ducks" film trilogy is the story of a man, born cancelled, named Gordon Bombay, who learns a valuable less about class prerogatives, while stoking insurgency in a youth hockey team.

Unlike other 90’s cultural touchstones for millennials like Blank Check, Kazaam, The Sandlot, and Jingle All the Way — all of which I plan to discuss in subsequent dispatches- this film doesn’t have an overt (but does strongly imply the need for a) call to arms about the corrupting influence of capitalism on the fundamental goodness of people, particularly of the millennial generation, but tells the story of a class struggle, intergenerationally, that seeks to guide us through revolution, ineveitable dooming oneself to ethical failure, and redemption in our guiding principles to reform an unjust system.

Coach Gordon Bombay’s story begins shortly after the death of his father, and seemingly being distraught over this, costs his own youth hockey team to lose, and internalizes this disappointment he feels for having, he felt, let his father down. He quits hockey, and becomes an ambitious, angry young man.

After his own coach, whose motto is that it’s not worth winning if you don’t win big, he becomes an effective, but not successful (this distinction will matter), attorney, but he’s arrogant, immature, and his frustration with not being made partner in his firm after his undefeated record in the court room, and his boss, Duckworth, telling him being a winner and being a good faith participant in the legal process are different things. He is winning big, but this is the first time Gordon is setup to fail ethically— he applies a purely unnuanced lens, if he wins, he is successful, and if he is successful, the meritocracy he thinks he is paying into, the world will reward. It’s not an unreasonable assumption, but it is an entitled one:

The nature of the District 5 hockey team is that they’re largely economically disadvantaged. They play the sport for the enjoyment of it, knowing there is a class stratification between themselves and the Hawks, the team from the wealthy part of town, of which Gordon had once been a part. He his assigned to coach them to prove to Duckworth that he can be a responsible member of society.

A running theme in the first film is this class division, and the kids’ acute awareness of how wealth disparty often means a lockout from every transcending ones material conditions without a leg-up in a system where social programs, etc. are often not available, or are means-tested to a point of unusuability.

With Gordon’s assistance, they eventually do overcome these material disadvantages to compete with the Hawks’ much larger resource base, and go on to triumph.

The second film becomes somewhat more complex— they’ve staged a local upending of a longstanding assumption about power and influence, but in selecting the Ducks to represent the US in the Junior Goodwill Games, they become the avatar for everything American; something Gordon immediately embraces, and something the team reviles. They are proud to compete for their nation, but feel their souls don’t need to be sold, branded, and packaged. This is an America we are familiar with— one looking for a fight, everything is adversarial, even a competition of good faith with other nations.

In context, this is 1994, so I want to make a point about the Clinton 90’s— far from a time of peace, but one that begins a slow simmer of combat without declaring war, and exemplifies the American desire to view anything that rejects our values as an attack on our values- the USSR had fallen, Yugoslavia still existed, Saddam Hussein was not yet a top priority for our nation’s leaders looking for a new enemy, Bernie Sanders had a couple years earlier contributed to the effort in the House to prevent incursion into Iran (to tell you how contemporaneous the figures in our narrative tend to be), and in a geopolitical context, things were comparatively tame (for a nation embroiled in imperialist military growth for nearly 50 years at this point) to where we’d be in another decade, and frankly, it seems, even the writers of this film could not avoid demonizing a country with lifestyles different than our own.

Iceland, in this film, is an avatar for the residual feelings about the conflicts of the Cold War with the USSR; instead, since Icelandic values are portrayed as being antagonistic and adversarial, the films broaches a different topic than mere intolerance, but casual xenophobia.

This is something initially embraced by the Ducks, newly minted representatives of the US empire, as they plow through Trinidad & Tobago, Italy, Germany, etc. only ot be toppled by these mysterious kids from Iceland. We simply ran out of enemies, and rather than look smilingly upon the fruits of the supposed meritocracy whose outcomes might be used to justify the superiority of American life, they are ascribed malicious intent, in an effort to *checks notes* win a competition rather than rollover for American exceptionalism. Does this sound familiar?

Let me divert here for a moment to drive this point home about 1994 in the United States; we simply did just run out of enemies to perpetuate global imperialist foreign policy. This is a decade where after arming and training insurgents in Iraq, Iran, the -stans, for decades to fight in a proxy war against the Soviets, all of the military conflict of the 90’s was comprehensible, but lacked the commoditization of Desert Storm, we had no vehicle for selling open conflict to the public without an avatar for vague evil.

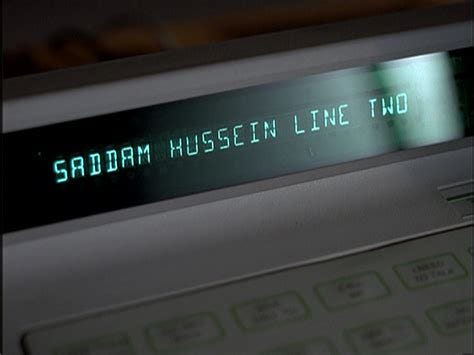

There’s an X-Files episode, “Musings of a Cigarette Smoking Man”, where the main protagonist of the series, my man Spender (“The Cigarette Smoking Man”), anonymously publishes a memoir as fiction; he details his role in conspiracy from the failure of the CIA in the Bay of Pigs, to the Kennedy Assassination, to MLK’s assassination, and ultimately, the cover-up of extraterrestrials, where he’s, per a compact made with the nation, forced to execute a captured alien, all while implying the UFO hysteria of the 1990’s was intended to imply a sinister force the government was actually fighting in the absense of one figure they could point to. The conclusion of the episode is around a board room table, where they are wrapping a meeting on Christmas Eve, and they conclude they’ve run out of things to do; America has finally “won”. The conference room phone rings, and it’s Saddam Hussein calling, and the Cigarette Smoking Man, in a moment of clarity here, muses that there’s, as a says at another point, “a solution to every problem”.

This is ultimately the mindset at play in this film: in the absence of cultural short-hand for adversarial parties, the mere implication of something to fear becomes the adversary; it didn’t even have to be Iceland, this doesn’t even actually make sense geopolitically, but that’s not the point, the “othering”, this time on a nationalistic basis, not a patriotic one, rather than the class division of the first film, and this is where its intended message loses focus—a metaphor for how social movements can fall victim of propagandization in their lens on their identities. You’re an American, you’re a Duck, you’re a patriot, you’re a fed, etc. above all else that might exempt you from the collective dialectical of how we relate to one another because of the mere implication of an extenuating circumstance.

Ultimately, Charlie, the team captain, and the Iceland players come to respect each other as peers— we were so consumed by the egos of the coaches, that we fail to consider, narratively, that those producing the labor do not receive satisfaction, even while Gordon self-flagellates for having lost sight of why they were competing. This is against the backdrop of a fractional US victory over a shootout, a nod to the true lesson of geopolitical conflict having an alternative, international labor solidarity.

The third film re-introduces us to the class struggle theme of the first film, but now with the wordliness of the experience of people outside of Minneapolis; they’re aware of a global struggle of the laboring classes. The kids are admitted to Eden Hall as the Junior Varsity team, but are resented because the anointed status of the Varsity team is challenged on its merit; they’re deemed charity admissions.

This film has an interesting element: Thus far, the series focuses on a class reductionist framing that does not consider race, but the inclusion of Russ Tyler, a black teenager from South Central, Los Angeles, adds commentary that applies a minimal lens on an intersectional basis: Sure, the Ducks are poor, but they are also white, he is not, and his success at the school is paramount to the success of not only himself, but his family. The framing from the previous film is that Russ’ family includes a brother roughly his age who, presumably, was not lifted out of whatever circumstance to be given this opportunity to participate in a system institutionally rigged against him economically, but also racially.

The inclusion of a black character was not new; Jesse Hall was in all three films, however, they never elected to make this distinction— I doubt this was intentional on the part of writing Russ Tyler- or really address that he was part of a very small group of black players on this team that ultimately does get singled out for being black in the narrative, so what gives?

There’s a point in the film where he says, “[Watching TV] was the safest thing to do in my hood” in response to a working class white teammate who says “Y’all watch too much TV”; this is the first time this is broached in the entire series that black and white Americans experience poverty very differently, and that, arguably, when the system isn’t actually built to oppress you, it’s more accessible for, say, Charlie Conway to rise above this class divide than Russ Tyler. This only comes up one more time when, while considering a revenge prank on the varsity team, Russ reiterates that he cannot lose his scholarship— the opportunity is simply too much to have chanced into overcoming into a fair shot at a quality education to pass up.

Ultimately, the showdown isn’t merely the victory over the Varsity team, but what they respresent; institutional, generational wealth— at one point, because of their performance on the ice, the board decides to prematurely pull their scholarships. Their new coach, Charlie, and now in-exile Gordon Bombay fight this decision, and Gordon, an alumni of the school himself, more of an avatar for the establishment than their new coach, Orion, threatens legal action to overturn this decision, on the basis of a universalist approach to education being the overriding ethos of why they are there, not to be qualified by their performance in “earning their keep”— they participated in this community in a contract, and that contract was being broken.

The problem with how this series ends is that the Ducks, ultimately, win their showdown, become accepted by the establishment, and this is, like all moderate revolts, meant to quell outrage by demonstrating better things are possible, without actually reforming the system that led to the injustice in the first place. This was a high-profile win for the Ducks, but not for their communities, or even other students who are being pinned down by the system. They rallied public support for their victory, but secured nothing but power for themselves. They can be inspiration, but were not the leaders of a movement to secure what they set out to achieve.

In the arc of world historical revolutions, this dynamic is one popular framing of the French Revolution of 1789: a gentry class and the monarchy fighting for power, the latter hyperextended on debt to the former, so the power dynamic is challenged. Because the gentry don’t have political standing in an official capacity, their position is easier to understand as somehow just, or at least more so than a monarch who requires them to perpetuate their kingdom. So, the peasants on both sides fight in the service of their leaders, and ultimately, gains are made, but for whom? Certainly not the common citizen— revolutions tend to become more extreme, historically, the more extreme the disparity that caused it tends to be, by the time of the Paris Commune many years later, this would be the closest the average citizen would get to the sort of institutional change that would resolve this disparity, at this phenomenon’s most extreme in France.

My point in bringing this is up is that, if we were to, for example, extend this series another 3 movies, and then another, it would be a great lesson in how power transfers through revolution— by D6, we might see Charlie become the coach of the Hawks, believing himself to be a revolutionary subverting the system, but the relative “poor team” from the wrong side of the tracks would see him as an untenable neoliberal cosplaying radicalism, and he is brought down by a District 5 Goon Squad, the event causes the league to disband, and this is settled in off-book rules street hockey pop-up matches, led by a lesser member of the original squad that was left behind in Charlie’s revolution, someone like Dean Portman or Jesse Hall, and after the resolution of another trilogy, the faults and hubris of the previous regime ultimately end up plaguing a radical revolutionary government, dooming the entire enterprise to the slagheap.

You get my point: this sort of media does a good job of demonstrating how class, race, can persistently experience inequity while making wins that are ultimately just concessions on the part of the ruling class, because perhaps of a ruling class advocate who empathizes, but ultimately remains in class solidarity— move the needle, but not so much that anything materially changes for anyone other than the symbolic win to the principals in the film.

You see this time and again in contemporary politics— make a modest concession that only implies to the oppressed that better things are possible, weaponize that concession to be propaganda for a meritocracy framework that doesn’t exist with the goal of shaming critiques of the system.

It’s a limited hangout! Imply the in-road exists, cop to a certain amount of corruption, but by controlling this concession in this manner, having thwarted open revolt, actually conceded nothing but the right to be openly bigoted, and even then, this is never really true. Charlie and the Ducks beat the rich kids, they change the school mascot, but no one truly loses materially, and the acceptance is for them, and them alone, not who or what they represent.

A more satisfying ending? Look to a film of this sociopolitical meta-narrative genre for children like Kazaam where the ethical conflict is resolved by the accelerationism of Shaq taking on a new mortal form, one like Blank Check where the fraud is recognized and no longer accepted as a social constant, but in the Mighty Ducks, it’s more of an exposure of the need for deeper (rather than broader) intersectional analysis in how to reform, than it is a guide to revolution.

Anyway, it’s no Cool Runnings.

Extras

Recent things I’ve read, listened to, or watched that I am now recommending:

Mac DeMarco - Ode To Viceroy - 3/13/2013 - Stage On Sixth, Austin, TX

Gore Vidal on Henry Rollins Show - Part 1 & Part 2

Michael Parenti on the US War on Yugoslavia