“It is not so much where my motivation comes from but rather how it manages to survive.”

The creative process may be a burden; does it persist out of necessity to human connection, purely a cudgel to remain productive, or a tool for empathetic perspective?

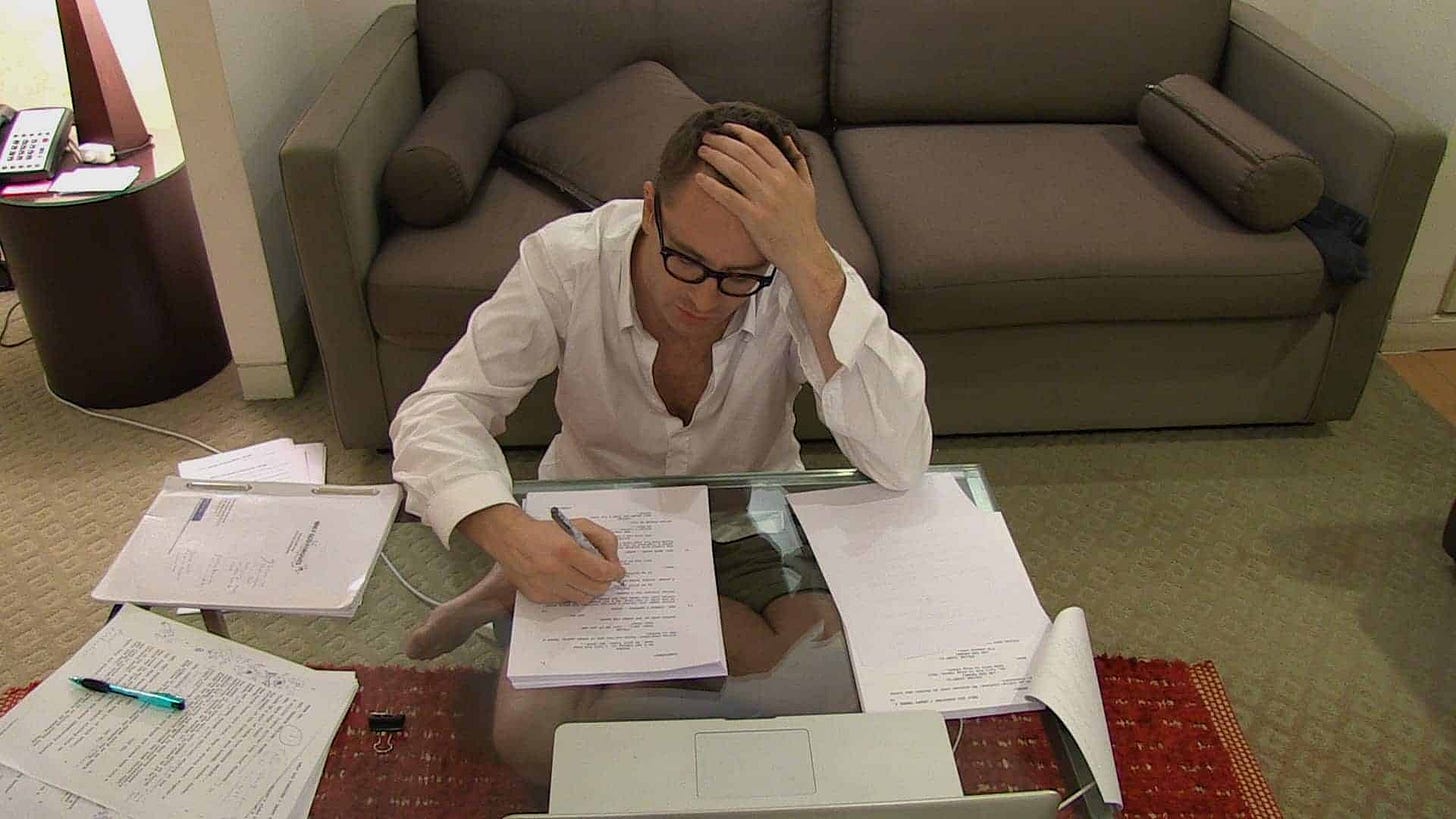

There’s three films I will die on the hill of believing incapulsate the emotional and cognitive rigor of creativity as vocation, two of them documentaries, and the other a dramatization that is, somehow, less bizarre and deranged than its source material, and I’ll discuss why these films in short order, but want to put forth that what they share is, like any good political revolution, the creation of great art is not done by committee, even if it becomes or was always intended to be the prevailing ethos of an artistic generation. Creating art takes its toll on the creator: one might procrastinate in the face of an unclear solution, waiting for the path forward to become apparent; the other might remain assured of their ability to figure it out to the exclusion of days and weeks of productivity and support and even the project’s main thesis, believing this is in the service of the art; some simply beat their head against a problem until it makes sense.

In Sketches of Frank Gehry, the documentary opens with a monologue by Gehry abour “getting started”: “Is starting hard?” Gehry asks, “You know it is…”. He speaks of the administrative work he does to avoid doing the thing he’s most known for, “stupid” things to “make sound important”, afraid that he “won’t know what to do”. Once he does begin, however:

Gehry’s chief assertion as an architect would seem to be that the shapes we see in nature can be made by hand as well; not bound by forms, or the substance of what makes one shape the shape it is, he designs by perception. A crumpled piece of paper need not be recreated meticulously to say a building was modeled after it, only the perception of having done so matters, that the shape he draws as its representation is a shape of the building through the end of the conduit, divorced from the context of its creation, only on what it became.

It’s holistic; the component parts and processes fail to make a building, unlike their function in nature— this is the function of creative method here, subtasks are not building blocks, they’re aimless without a return map from the completed vision, only then does the path become navigable.

In Greg Sestero’s memoir The Disaster Artist, as well as the film adaptation of this book, he details his years spent with Tommy Wiseau creating The Room; a story of a man who wants to be a great actor, be respected for his craft, and the only problem is that, well, Tommy can’t act. Ultimately, inspired by the events of a mysterious past, and a friendship with Greg beginning to crumble as Tommy’s resentment over Greg’s comparable success grows, sealed by a screening of The Talented Mr. Ripley, Wiseau writes, directs, and stars in The Room. The film is a sort of post-modern Ripley in that it mirrors the conflict, except that the relationship dynamics, to say nothing of the plot incoherence and continuity errors that have made it a cult classic (and a hero of Wiseau in his own respect), are completely inscrutible.

At one point in the story, Wiseau, a successful business owner, lays out to Greg his vision for himself; he wants his “own planet”. He wants to be notorious, not merely successful, and in his estimation, no lack of talent and acceptance can’t be overcome by brazen, deranged self-congratulatory confidence in one’s own abilities. I won’t say The Room is a masterpiece because it’s good, but that it’s entertaining as mythmaking, the many moments of surreality— this film is the closest you can get to being inside the head of someone with an extreme, but ultimately innocuous, case of being totally warped by the Dunning-Kruger effect.

In The Disaster Artist we get a glimpse into how Tommy believed himself a vampire, and would work that way, too; he was self-assured, but needy, he was a terrible leader, but a committed creator. That he saw the outcome of major Hollywood filmmaking due to him, while rejecting the order of things required to get that outcome traditionally, he exposes The Room’s success for what it was; a cultural watershed of, not merely so-bad-its-good, singularly telling cinema about how, if asked to imagine in one’s own head the biggest grudge you’re holding in your head irrationally, unhinged anyone’s narratives of conflict and ideation about everything from catching an opponent in a lie to literal suicide (in Tommy’s grandiose words “In front of the whole world! They will be shocked!”). He’s inadvertently asking the question, “If your innermost fantasy of resolving conflict in your life were a movie, would you be able to dissociate your emotional response to what is realistic and probable rather than merely irrational and satisfying?” The answer is that, no, probably not, it’s an insight into creativity in the same way it’s an insight into the kind of art one creates from an unrefined sense of trauma in one’s own life.

In My Life Directed by Nicolas Winding Refn, we follow Refn on a journey to complete the making of Only God Forgives, and it’s notable for a few reasons; it’s not just Refn’s journey we’re seeing as a creative, and the administrative decisions that can stunt creativity or enable it, but we see the star, Ryan Gosling, observing Refn throughout. Gosling would go on to direct Lost River not long after this, and it’s as you’re seeing the development of his creative lens from that of performer to director. Refn and Gosling, basically, spend much of the film, either, agonizing about the cost of completing the film, or when he is in creative-mode, about to lose it over how long resetting after a botched attempt at a stunt will take.

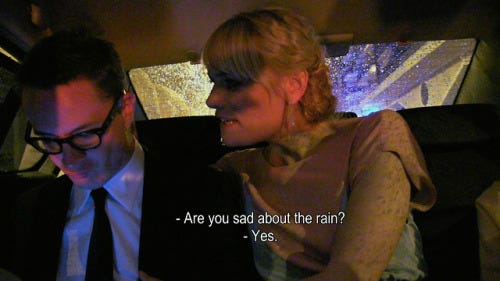

He keeps his cool, but barely, and it almost eats him alive— his wife, the director of this documentary, Liv Corfixin, frames this film in the context of his previous effort, Drive, being an isolating experience for him without his family, so they relocate to Bangkok for the duration of shooting. He doesn’t fare much better this time, but his family seems accustomed to his harsh self-critique, they hold him to his obligations at home, and ultimately, it’s his daughter who tells us the real reason creativity should never live or die at the hands of commercial critics:

He completes the film, and en route to the premier, his wife asks him is he’s upset about the rain (he believes this to be bad omen), he replies that he is. His daughter chimes in at this point:

It’s a devastating insight into what makes this documentary about one man’s professional stress such a compelling thing to watch; it’s not that nothing you create will ever matter to anyone else as much as it does to you, but that your critique of it, your perception of critique, will always be harsher than that of your worst critic’s. You make a film, and if people don’t like it, or are left unsatisfied by it, or worse, have something negative to say about it, then, as the child might say, you lost nothing by trying. You try again, and you let your methods, the sublimation of these anxieties like Refn does, like Wiseau does, and yes, like Gehry does, into expression (however coherent) of what you plan to share of yourself.

This isn’t just about film, or depictions of creative process, but about why that process exists and what function it serves: “Start your own band, paint your own picture, write your own book.” was something the San Pedro band the Minutemen believed; self-described “corndogs” who had no sights on competing on the basis of their aesthetic, instead relied on sheer force of will to produce, in their short tenure before lead singer D. Boon’s untimely death, a body of work that’s a testament to the beauty of working class struggle to reclaim the most human of all endeavors, creative ambition. Operating their band along strict, ideological lines, what they hoped to come of all of this was obvious; Boon used to say he was “religious about man”, and what is not more expressive of the liminality of the continued expansion of humanity’s capacity for growth than the continued commitment to creation, and collective interest in the society, along the lines of personal expression.

Extras

Some things I’m reading, watching, or listening to that I am now recommending:

Monthly Child Tax Credit Would Be a Trainwreck - People’s Policy Project

The Fire Last Time, Elizabeth Bruenig

The Hour of the Barbarian, Vincent Bevins