File Under "Obsession"

Meditations on neuroticism in the class struggle, and the role of obsession in sidestepping ennui

This one will be less formal than most, and is more of a lamentation about creativity, the role of individuals engaging in personal introspection in the service of mass movements of varying types for cultural commentaries:

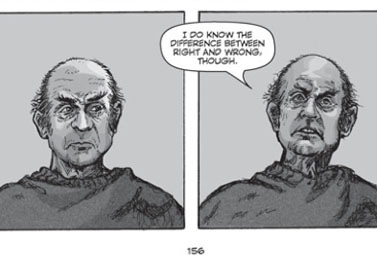

I recently re-watched the 1994 Terry Zwigoff documentary Crumb (filed under: “Weird Sex” and “Obsession” on Letterboxd), 6 years in the making, about the cartoonist Robert Crumb. I was never a fan, or a follower of Crumb’s, but my interest in comics was always somewhere adjacent to his orbit; as someone who identified deeply with Harvey Pekar, I think there’s something to the idea that for every perverted visionary like Crumb, there’s a repressed, uptight best friend who has the ideas, but not the technical ability to execute on that, partly because they’re so uptight, and that was Pekar, and, at least in my mind, myself.

Harvey Pekar’s Cleveland became, throughout his career, and well into the new millennium before downtown Cleveland got revitalized, and professional football had solidly returned to the city, synonymous with the sort of working class mythmakers like himself, and to a lesser extent, Drew Carey, but also “weird” culture the same way cities like Austin, TX and Boulder, CO like to pretend they are in the form of Pekarian cariactures like Toby Radloff. Crumb’s Rust Belt, with it’s hippie-era San Francisco tinting, seems like the cool older brother in comparison.

What always struck me about Pekar’s American Splendor is not that, as with mainstream (but equally insightful) depressives like Charles Schultz, in reality for every winner there also had to be a loser, but that there’s a case to be made for sublimating life’s irritating minutiae into countercultural commiseration with someone who, otherwise, mutually, you’d have nothing to do with each other.

The former-Pentecostal Clevelander, Drew Carey, for example— Pekar, noted politically left, and Carey, an avowed libertarian (or, as he put it, “a conservative who gets high”) have a lot of common ground that has a lot to do with the depiction of Cleveland as a policy failure for the working class— it’s a representation of this demographic middle of the United States in Chicago, while Cleveland is the dump site for this assumption’s dark side.

In Carey’s memoir, he tells a story about his political disaffectation in the early-90’s during Bill Clinton’s ascendancy to the presidency, where he tells the young men and women of his generation that it’s time for them to make sacrifices for the greater good, a good message in theory, while Clinton excessively wealthy himself, even at this stage, amongst a class of yuppie elites; Carey, then living in his car, sees nothing of himself in the bogus populism of the Democratic Party.

Harvey Pekar spent his adult life working for the VA, an institution known for failing its constituents, but even for its employees, provided little more than a living to people like Pekar, who for example suffered through cancer while employed there, and many of these experiences of living through policy failure turned into art. This is somewhat reflected in The Drew Carey Show’s fictionalization of Carey’s life as a middle manager for a department store’s executive suite— his commitment to free markets and the capitalist system, he must repeatedly learn, comes with no guarantee of fairness or equity, and ultimately, that he fails to evaluate the failure of ideology is a metaphor for the United States in 2020, something Pekar accepts, however, early on, rather than it becoming a platform, it becomes the message. This is practically McLuhan-esque in its framing of these two pieces of media meant to tell some kind of higher truth about the working class. How do you activate someone for a politically progressive cause when their experience with the supposed progressives in their party duopoly system don’t seem interested in anything even approaching economic disparity resolution? For many, they come to the conclusion that the duopoly is a false choice, as many binaries are, but this can take a lot of different paths depending on a number of personal factors for groups within our society.

Something forward-thinking about Pekar, however, that I feel applies outside of the microcosm of Cleveland, and applies to American Jews of my generation, is his disorientation when it comes to the state of Israel, the role of his cultural Judaism, and how this squares with a multicultural leftism, something of supreme relevance today, while the class struggle he and Carey discuss remains highly relevant, but only becomes amplified through this lens of precedential religious/cultural politicization.

Pekar, later in life, became conflicted about the messaging, goals, and intention of Israel, as he witnessed the plight of Palestinians; regardless of how you feel about this issue, and I won’t go into my (well-covered) views on this, it speaks to a global community minded approach to lasting, sustainable solidarity for all humans to consider where you might’ve been propagandized to, on some level or another, in favor or opposition to any given issue, no matter how you came to these conclusions in the first place.

In the Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn frames part of this narrative in the context of the transition of power from Stalin to Khruschev, and the subsequent shifting of power away from Stalinization and authoritarianism, with a mind on socializing (in the context of democratizing) rather than persisting in the post-revolution ideal of healing the ills of the illegitimate, failed state of the Russian Empire through varying levels of compulsory redistribution that Stalin extended as a means of control well past the need for this manufactured state of scarcity— that it didn’t work out this way isn’t immediately relevant, but the notion that intention can diverge from execution, or that regime change can impact one or both of these things, means that the same action can take on dramatically mutated import. One can view this as a concept and an execution with a lot of nuance, and hold both of these thoughts in their head simultaneously, and for many, the same cannot be said amongst American Jews, for whom dual-loyalty is a heinous smear, but remains a blindspot when considering the investment of lobbies like AIPAC in creating a single coherent narrative to either agree with, or face the consequences.

Pekar puts this somewhat relatably, and a little surprising for someone of his generation; the Israel we got is not the Israel his parents (Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants from Poland), and more broadly our people, were promised, and that promise did not include a credible, contemporary case for crimes against humanity; a source of deep emotional and ethical conflict for many, not just himself, in debating the incongruity of being a progressive and the conditioning in American Jewish education towards unequivocal Zionism as a function of Judaism, rather than the latter informing the principled stands for, or against, social justice causes.

Whatever your position, again, on this issue is, it’s undeniable that it’s a situation that is being packaged to discourage critically examining things in solidarity with fellow humans to remove the context of nuance and the fluid nature of geopolitics, as well as domestic socioeconomic dynamics in saying that there’s a single right, or good, answer, or to take the position that, in order for someone to win, someone else must, necessarily, list.

As Pekar demonstrated presciently in highlighting, this is of heightened relevance in 2020: in times of great social upheaval, notably in the rise of fascism during the last century, culturally Jewish people have often looked towards this part of their background for guidance/solidarity for the cause of a greater social justice; you see this with people like Albert Einstein during WWII, the commitment of the Manhattan Project scientists (Oppenheimer, for example, cited the atrocities of the Germans as a motivating factor, as a Jewish person, for participating; Feynman, similarly, but in not so many words, contributed on this basis as well— that, ultimately, the weapon was not used on Germany is, again, an example of intention and execution diverging, and this identarian aspect taking on an ethically conflicted aspect in the mental calculus of “how to be”), and Pekar, in his conflict over how to be an activist for the causes he found himself at odds with his community over, while also being a victim of policy failure as a civil servant himself.

Part of why I feel an immense amount of inherent empathy, before whatever else I might feel about them, for someone like Drew Carey (he, himself, is doing fine) is that, like many people of working class backgrounds, he sought opportunities and performed hardwork as a function of believing it would secure him a living; for his part, Carey was a Marine Corps veteran, and found himself abandoned, like many vets do, by the bipartisan state. This can lead you down some weird alleys, and it doesn’t pay to necessarily shun those whose conclusions are incongruous with your own, or the acknowledged outcomes of a given lived experience. The question this should be raising for many is, “What is the failure here?” even if you choose not to discount the role of individuals in systemic issues (which, of course, is fair, but what does it accomplish to hold an individual accountable for a systemic issue without addressing them as a byproduct of said system?)

Life gets dramatically more complicated, precarious, even openly dangerous when you add factors that compound and similarly stack the deck against you in society (as we’ve seen, for example, with police brutality— summary execution by the state, in many cases, for the crime of being Black in cases of people like Tamir Rice, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, the list goes on and one), which is what is meant when someone is asked to consider something intersectionally. For Carey and many working class people of all races, it was poverty, for Pekar it was his religion as well as his class, for many others, it’s so many other things, which I think, both, made an attempt at depicting to some extent in their work beyond just their own personal narratives the lives of those with a lot more working against them systemically than themselves.

A couple years ago, I read a book by David Shapiro called Supremacist, it details a fictionalized account (in the book, he’s jobless, not a semi-retired corporate lawyer; a spiritual sequel to his first novel, a roman à clef) of his trip to visit every Supreme store location. Ultimately, like most things, it’s not quite so simple: he feels the brand and it's aesthetic gives him something to think about, obsess over, and commune online in the active resale market for their products, it’s the work of a supremely lonely person, but one who fundamentally understands coalitions, without the ability to participate in one— he even has a traveling companion who quickly loses patience with his mission, someone he’s known for years, but has routinely alienated during their friendship, and this trip is a microcosm of that experience of aimless passion that, draped in consumerism, fails Shapiro ideologically, like Carey a generation earlier, and Crumb the one before that in his pursuit of art work through card design. Capitalism is the corrupting factor, at best, consumerist logic the biggest saboteur, speaking purely pragmatically as a function of the economic system we all contend with.

In The Character of Physical Law, Richard Feynman talks about certain things in nature that, if approached naively (“if you were different…as if you’d never seen it before” as he put it in a related lecture), becomes an exercise in understanding from context for the common features of natural phenomenon, rather than relying on your knowledge, biases, etc. (an imperfect, but introspective method for examining what biases you might be predisposed to use as a lens); “the thing that make the wind, make the waves” as he would put it in another lecture. From the subatomic level to the schema of interpersonal relations, and that of parasocial relationships with our institutions; in the US, as it was for Shapiro, it was a brand, for Pekar, it was the state, for Carey, it was the markets, and for Feynman, it was the universe— how solidarity works rarely changes, conceptually. For Robert Crumb, it followed this pattern as well, however, even as far as solitude goes, Crumb indulged, rather than combatted what set him apart socially; choosing the itinerant life of an artist, while eventually becoming successful/sustainable, was not a smooth on, and one that prioritized the creation of art ranging from the ironically perverted, to the satirically insightful, to the often controversial, but unified by the notion that there was something to humanity to be observed and depicted and a narrative told about it. The overarching narrative of all of these brands of struggling to contend with how to be a better society, or a functioning member of it, is that there’s obsession, anxiety, insecurity about being afraid of being wrong, and neglecting that notion proving to be the key— all of these figures were activists for something, their personal experiences informing their commitments, if not being the motivator for said empathetic response), and how to approach this, or what the role of the individual looks like in a systemic response; countercultural iconography, universalization of understanding, nihilism, or characteristic ennui, all misunderstood to be apathy, but are foundational in the expression of many.

Extras

Recent things I’ve read, listened to, or watched that I am now recommending:

What Mills' "Power Elite" Can Teach Us

Michael Parenti - The Darker Myths of Empire: Heart of Darkness Series

The Shadow Factory: The NSA from 9/11 to the Eavesdropping on America - James Bamford