Architecture parlante

Forms in modernity have become dogmatically self-defeating; an art culture of the professionally and perpetually exhausted

The book The Soul of a New Machine opens with an anecdote from a bunch of professionals like a banker and a dentist taking a vacation operating a sailboat, and the professional on-board taking the most shifts, Tom West, a computer engineer, doing the most grueling work, was a guy who wouldn't say what he did for a living, what his job was like, or anything:

The people who shared the journey remembered West. The following winter, describing the nasty northeaster over dinner, the captain remarked, “That fellow West is a good man in a storm.” The psychologist did not see West again, but remained curious about him. “He didn’t sleep for four nights! Four whole nights.” And if that trip had been his idea of a vacation, where, the psychologist wanted to know, did he work?

The significance of this anecdote is that often the key to being perceived as a legend in your field, while being a self-acknowledged cog, that something can be your life’s work and still not be something you care to make your entire life and so much so that your conception of what is, and is not, work defines how you the experience of human’s place in nature:

A snapshot taken of the cockpit in the afternoon shows West sitting in the stern. The dark shadow of a day’s growth of beard reveals that he passed adolescence some years ago, though just how many would be impossible to say. In fact, he is just forty. He wears glasses with flesh-colored rims, and a heavy gray sweater that must have given him long faithful service hangs loosely on his frame. He looks as if he must smell of wool. He looks thin, with a long narrow face that on a woman would be called horsey. A mane of brown hair, swept back behind his ears, reaches almost to his collar. His face is lifted, his lips pursed. He appears to be the person in command.

One of the crew would remember being alone with him on watch one night. They were sailing under clear skies with a gentle breeze. Suddenly, at the slackening of the tide, the wind fell away, some clouds rolled in, and then just as suddenly, when the tide began to run, the sky cleared up and the breeze returned. In a low and throaty voice, West made exclamations: “Did you see that?” He made his low and spooky laugh. His companion was about to say, “Well, I’ve seen this happen before.” The tone of West’s voice prevented him, however. He thought it would be rude to describe this event as ordinary. Besides, West was right, wasn’t he? It was strange and wonderful the way the pieces of the weather sometimes played in concert. At any rate, it was fun to think that they had just encountered a natural mystery, and, somewhat surprised at himself, West’s companion suggested that events like that made superstitions seem respectable. West gave his low laugh, apparently signifying agreement.

The nature of experience is that you can decouple your work from the aspects of it that are supposed to make it your passion as vocation in the first place, and the common thread is work, as such, capitalism, etc. makes the spectacular things about what each of us does seem mundane, routine, devoid of discovery in some way, as West reminded the crewman.

But what about the inverse? Not experience, but the human role in nature; creativity. What if the person who executes a particularly ambitious has to be the one to try because the form is at risk of extinction? Is that more human than the impulses of someone like Tom West, or less because it is entirely about the work, and of passion, and ultimately something that will prove difficult?

The first time I saw Cameron Carpenter play the organ, it was in the context of a (n admittedly, extremely funny) joke:

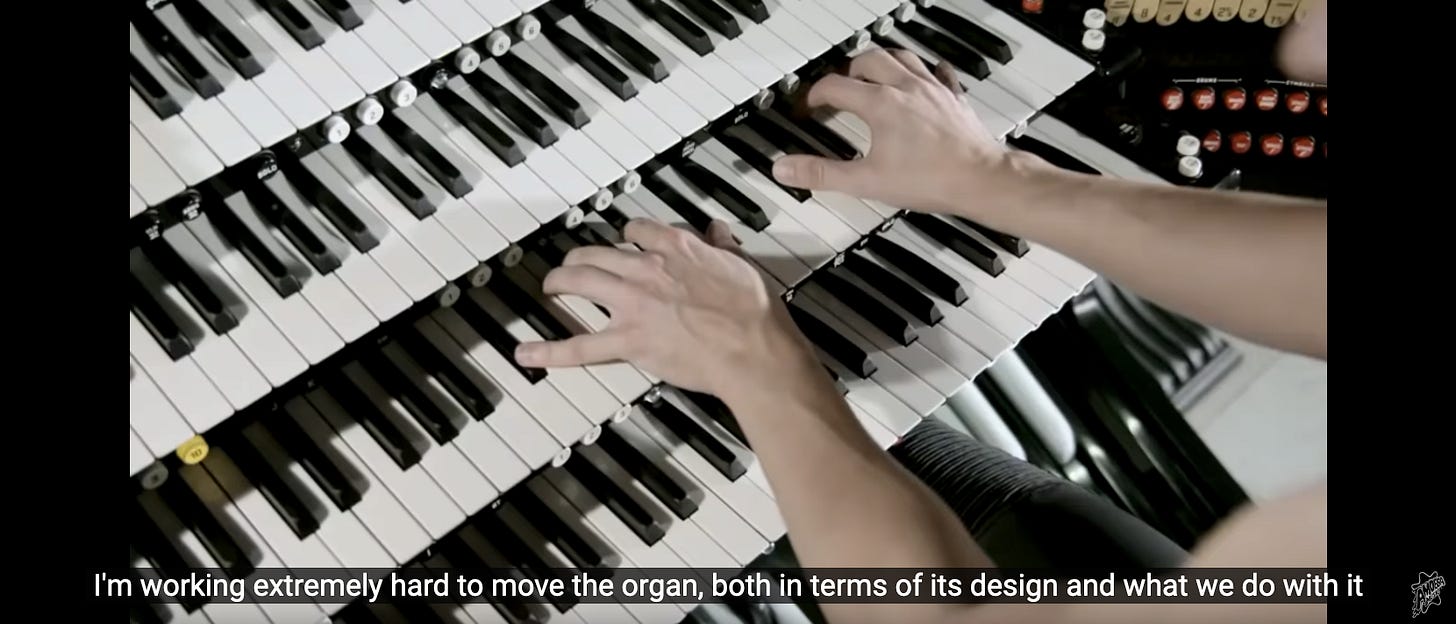

But I became fixated at some point over the last year. Fixated on the idea that, rather than being confined to viewing streams of Carpenter playing an organ in a church or concert hall online, what if I could see this in the flesh? To the purists, it seems offensive to make a commercial enterprise of organ playing detached from church and concert hall installations, but to me, it sounded like something I needed to see for myself.

The Platonic ideal is the idea that a thing can be so about itself that it exemplifies the thing so perfectly as to become synonymous with the qualities of that thing. Carpenter’s persona aside, his commitment to the craft is undeniable, it makes me trust him and his intentions more knowing that this isn’t coming from a place of installation organs making him sound bad or whatever, but from a place of wanting people to hear it where they go. When I watched a video explaining why he wanted to make an organ detached from time and place, so he could play anywhere (and it’s really not as portable as one might think, at least not for a single performer), I became curious when he admits this is “not rational”:

He wants to assemble a “new character”.

We’re not talking about reinvention, we’re talking about evolution, and sometimes that takes a personality so cringe that he makes weird rhetorical missteps about something he understands, but is underprepared (either, incapable, or because it is impossible) to articulate rationally, while remaining absolutely correct to reflect the next step for that instrument’s history, even if potentially a misstep. In the case of the organ, if confined to the original confines of where you’d see one, was that space integral or incidental, typically in context, to the instrument? Modern advances in musical technology to approximate any space with (I say this completely sincerely) complete sonic accuracy notwithstanding, I think the exercise demonstrates that the physical presence of an organ is not part of its Platonic essence of that an organ is or how it’s played, and that the proliferation of a “touring organ” is a democratizing one.

With Carpenter, specifically, he describes his craft with self-awareness of its relevance, and with the knowledge that it requires drawing heavy-handed parallels to contemporary culture: he describes himself as “addicted” to graphic design, believes film scores to be a tremendous vehicle to perpetuating classical music, and in his pursuit of this, the organ becoming an accessible instrument while sacrificing little of the experience of playing one, performing on one, or listening to one is a tremendous undertaking that, as I would argue, only someone proficient in these things, at odds with the aims of the interests underwriting this effort, is qualified to assess the risks of doing so to the culture.

Ultimately, what seems to make people bristle about Carpenter, besides perhaps his unusual and somewhat obnoxious personality, is that he breaks the form of what you’d imagine someone who is a classical musician, an organ player no less; he’s not a dogmatist, and in fact believes this to be stunting the necessarily consequential evolution, not protecting from the commoditization of, this instrument. The obvious question is whether or not this can be done without it becoming a poor facsimile for consumer grade organists, inasmuch as such a market exists.

I think the larger impulse at play, in both of these cases, West in the 80’s and Carpenter a few years ago, is that it’s an effort to reconsolidate and refocus the energy humans spend on work, as either just what one does for a living and not what one is (West), or that what one does can be representative of what they view as important about being human that happens to be their job (Carpenter). On the surface, these things would seem in opposition; the late West might even have given you the impression that he’d probably not be having a good time in 2021 given what has come of modern computing, and Carpenter is all about figuring out how to leverage technology to advance a form he is also deeply defensive of its integrity. You could argue it’s, as much as you could a reconsolidation, a devolution, but not a regress, it’s a rehabilitation, a restoration. The question, then, becomes: how do you safeguard the balance between the excesses of a systematized, tentacular technoculture, and the borderline personal Luddism practiced by many working technologists who avoid “Smart Technology” in their personal lives after working on it all day?

In Adam Curtis’ 2011 miniseries “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”, he says that the stated intentions and implementations of these technologies and systemic approaches to social and economic problems by world leaders, more broadly, were described as “scientific, and therefore neutral”— encompassing everything from the Greenspan years in the Fed to the proliferation of Randian libertarian idealism’s influence over the autocratic function of state by the likes of technical leaders like Larry Ellison and Bill Gates. The answer to the above question, with this in mind, is to demand the nuance, the critical theory to recognize corporatist ursurpation of public power, draped in the language of science to imply objectivity, and that data can have no nuance, when the opposite is most demonstrably the case— the work of doing this never ends, which is why acceding to the order of these sociopaths as scientific geniuses is a grotesquely pat way for the public to accept, but not admit, defeat because, ultimately, the systemic nature of this impact is not combatable by individual action, the nature of Randian protagonists who produce nothing but are lauded as geniuses, figures like Elon Musk today for example, erodes the collectivized incentive to push back in any meaningful way.

Curtis’ thesis is that we’ve been colonized by these machines, and in so admitting, we’re being colonized by arch capitalists, elevated to the level of influence of statesmen, but also diplomats, not between nation-states, but the supremely self-interested party abstraction, a corporation. By comparison, the precepts of West’s machine, and that of Carpenter’s, are seemingly much easier to understand— West spends much of the early part of New Machine concerned with architecture, that of his own machine but that of predecessor machines and that of competitors. This is in the era of a pre-Internet, so much so that this being the conduit for nearly all information would have been laughable to West. West’s daughter, a librarian, likely could’ve told you better than he could’ve how a global network of computers, some more powerful than many multiples the Apollo LEM computer that now fit into every single American’s pockets, would influence the approach of these industrialists to the public’s consumption.

In this way, I see Carpenter’s machine as making that latter, prescient approach: You don’t need to push the instrument forward, you need to make the delivery more accessible. By protecting the form, you direct resources to the expression; if this is possible with a musical art, and some have suggested it isn’t, delineating the harmful aspects of the toolchain from the ones that increase the chances of success of his goal (a portable, but uncompromised organ for touring).

Curtis, himself in a 2004 interview, says, “what I am getting at here is that electronic community is a commercial enterprise that dovetails nicely with the increasing trend towards dehumanization in our society: it wants to commodify human interaction, enjoy the spectacle regardless of the human cost.” This, perhaps in a cynical interpretation, implies maybe this delineation isn’t possible in technologically advancing culture, but actually the warning is of the reverse, that this commodification is the dehumanizing incentive, not the technology itself, that perhaps absent commodification (capitalistic intent, self-interest, etc.) incentive exists, the technology can be harnessed. This where, I think, both, West and Carpenter stood to thrive:

West’s computer was anomalous in many ways from others being built at the same time, it was thinking about the user’s need and not the user’s present desire, for owning such a machine. Carpenter’s main duty, it seems, as I said, was similar to the form. Where this goes wrong is, for example, in computing when computer models are rehashed for ostensibly deeper market penetration (we saw this several times over Apple Computers’ long history, with more and more specialized variations) that exist purely for profit motive, and in the case of consumer musical instruments that increasingly integrated, and often to the detriment of sound quality, electronics into amplifier and, notably, synthensizer technology, which was the pitfall Carpenter could have easily fallen into under sufficient pressure from his patrons— that his vision stood to be more profitible for the larger investment was immaterial, if the goal of capitalism is to generate the most profit for the least amount of investment (and as a result, delivering, by definition, the lowest passable quality product for the price).

The mind trap Curtis seeks to demystify is that the collective trauma of modernity (war, collapse, proliferation of everything we’re taught to fear when aided by technology) against the backdrop of utopian ideal for any given situation, which appeals to an exhausted and traumatized public for its emphasis on solving nameable problems, while we see technology intersect, in more obvious ways, every facet of not only public (political, economic, philosophical) but also private (the sort of cop behavior online that does the work of the surveillance state but on an interpersonal level) life towards a paradigm of control we’re, seemingly (but not actually), inflicting upon ourselves.

Étienne-Louis Boullée is an example of an artist that, in architecture in this case, practiced what was derided as architecture parlante, or an overexplaining of function rather than letting the form speak to an enhancement or expression of that function— you only knew what it was because the building told you, rather than letting it serve its purpose or that common features of the purpose it served in surfacing. I was discussing this with my wife earlier: We walk together most evenings through our community in a neighboring complex of pale shadows of even McMansions— affordabilty built, but expensively sold townhomes and tract housing. This is the modernists’ dream for housing in 2021 if, however, they were affordable— that they wind up bulldozed in a decade would be immaterial if anyone could afford to live there sustainably. Instead, it’s a monument to capitalist overwaste, and the only reason you know who these homes are for? The signage declaring them “luxury” homes, built to order, from the shittiest materials the (over)developers could find to fill out every last inch of Eastern Iowa.

I mention this because, rather than try to evolve music using the tools of technology as one vector for growth, the arts follow this seemingly innocuous, potentially democratizing course often: the consumer access to digital audio tools, for example, didn’t primarily make it easier for musicians and composers to produce art they might painstakingly craft anyway using analog tools, it became an easy way for capitalists to forge a market from software patches and soundpacks to make overproduced music sound identical in composition as well as production. So, as a result, the valid art one produces with these tools are seen as shoddy or unoriginaly or “just pushing buttons”, but inherently considered lower art— Carpenter, in taking a highly elite instrument with a dogmatic culture of standards and fusing it with modern musical technology while seeking to preserve the integrity of the instrument for the listener as well as the performer, is demonstrably addressing this, whether you agree with his assertions or not.

The connection may not seem so clear, however: architecture that attempts to indicate what it is, in a culture that no longer recognizes a feature in the innate grammar of public imagination (and thus the form is not recognized, or contraindicates what it is requiring correction that denies the corrective nature of revision itself), that uses the old ways to say this something is right and good, or perhaps just well-executed (think a tomb for a European aristocrat in the mold of an Egyptian Pharoah— we know a monument when we see one, but that isn’t what makes a pyramid a Pyramid; the resting place of a God King and his court is not communicated by such a monument centuries later, culturally or religiously). One, ironically, violates the form by telling you what it is, when your eyes tell you something different, just as it does when the form tells you something that no longer applies to modern society— that results in disuse, neglect, and misappropriation of that form.

Consumer culture often relies on the coopting of such cultural and signifier-laden neglect; record collecting, for example, has its origins in preservation and archival for the sake of the art, with condition rating being a function of playability and thus fidelity of the audio, condition of the acquisition for its form, the message and not the medium. In the present, however, it’s a signifier of value, and in so (de)volving, a sealed and unplayed record of rarity has more value than the art recorded on it. It violates form and it corrupts what that form represents— Carpenter’s organ, in this case, represents a snatching of the instrument from, both, the institutions that would bar its propagation into the hands and the gaze of the commons, but also the corporations that would lessen its quality to make it consumable, in favor of the path of a creator to (re)define its use with the singular purpose of its being (to be played, played well, and with sonic presence) “the real thing” even if the form evolves. Conceding that there’s little, if any, ethical consumption under capitalism, it seems Carpenter strikes the appropriate, albeit cynical, balance.

The real significance, with all of this said, is that an effort like Carpenter’s, whether you agree with his project or not as an exercise, is that the act has significance, it’s recognized, itself, in its own expression— reclamation, not rebellion, but coarse (rather than fine) revision. There’s a reason Modernism would supplant this notion of parlante, and it’s because quibbling and coopting of form-as-utility became self-defeating, unproductive, and in the case of public structures, inaccessible— there’s a reason the artistic movements spawned from modernism resonate with any revolutionary movement’s aesthetic for progress from architecture to protest art to the politics themselves. The utility of function reasserted, the operators of a structure, a tool, or whatever become the arbiter of shaping its present.

Carpenter tells PBS that, “The authority ultimately lies with the individual listener”

I believe I understand his intent here: Carpenter notes he completed his organ, designed in part by architect Frank Gehry (a figure I’ve written about before), around when his father died; he’s asking the questions literary criticism asked long ago, does the author’s intent matter, does the author’s conception of the future matter, does poverty of the imagination (if only temporally— the notion of capitalism being foreign, for example, to then-contemporaneous feudalism; “who would choose this?”) play into this at all?

People don’t like Carpenter, for any number of reasons (which I totally understand), many believing he’s ultimately an opportunist seeking a profit, and maybe that’s true, but I believe, again even if true, this still presents the same questions for review of this effort in the same philosophical context— what else are we avoiding modernizing? Today, it’s the fine arts, tomorrow it may be the basis of something much larger, but far less human. Consider the preponderance of quantum computing companies— I believe the limitation there lies in classical computing understanding of how, both, classical computer systems engineers perceive the laws of physics, and how theorhetical physicists understand the tools for building and executing on classical computers; there’s a brick wall in there somewhere. How do we solve this without challenging long-held dogmas we might, otherwise, perceive as constants in the universe? Well, it starts by challenging man, ourselves, to interrogate why our own creations are limited by our own prescriptive forms of what that creation is.

This thing cost $2m, and took over 10 years, to build, Carpenter ascribes its completion to: “Technology, and my love of music.”— You have to ask yourself, if Carpenter were a less talented person, if the fusion of expertise and awareness of technological potential were enabling or mitigating in producing this end result.

Extras

Some things I’m reading, watching, or listening to that I am now recommending:

John K & Billy West on Howard Stern circa 1996

Rarities Vol. 1 - Legends of Rodeo

It’s the Petit Bourgeoisie, Stupid